Religions, individuals and Native American communities in the United States

Abstract

How has the treatment of Native Americans from the Colonial Era to present day denied the settlers more in-depth knowledge concerning tribes and their religious practices based on spiritual beliefs? The Native American spirituality used to be one of the main approaches and practices that had to be fought against, until its disappearance and therefore until the Native Americans’ adherence to the American mainstream way of life, the “normal” one. Yet, despite all the colonial and different federal governments’ efforts, Native Americans did not cave in, at least as far as their spiritual beliefs were concerned. They kept on passing them through generations. Today, these beliefs that have spanned many historical periods made Native Americans strong enough to adapt to the American society without leaving their religion(s) on the individual and community level. Does the resilient Native American experience prove that ignorance acts as a plague that feeds hatred of the other and of difference, and in this precise case, can faith in the broadest sense of the term be a means of survival?

Key words: Religion; Native American; Spirituality; Culture; The United States of America

Religions, individuals and Native American communities in the United States

Résumé

Comment le traitement réservé aux Natifs Américains depuis l'époque coloniale jusqu'à aujourd'hui a-t-il privé les non-Natifs d'une connaissance plus approfondie des tribus et de leurs pratiques religieuses fondées sur des croyances spirituelles ? La spiritualité amérindienne a été l'une des démarches et pratiques à combattre, jusqu'à sa disparition et donc jusqu'à l'adhésion des Amérindiens au mode de vie principal du courant dominant américain, celui de la « norme ». Malgré tous les efforts des colons et des différents gouvernements fédéraux, les Amérindiens n'ont pas cédé, du moins en ce qui concerne leurs croyances spirituelles. Ils ont continué à les transmettre de génération en génération. Aujourd'hui, ces croyances, qui ont traversé de nombreuses périodes historiques, ont rendu les Amérindiens suffisamment forts pour s'adapter à la société américaine sans abandonner leur(s) religion(s) au niveau individuel et communautaire. L'expérience résiliente native américaine prouve-t-elle que l'ignorance agit tel un fléau nourricier de la haine de l'autre et de la différence, et dans ce cas précis, la foi au sens large du terme peut-elle être un moyen de survie ?

Mots clés : Religion ; Natif Américain ; Spiritualité ; Culture ; Les États-Unis d’Amérique

------------------------------

Rachel Fondville

Docteure en Sciences Humaines et Sociales

Chercheure indépendante

Cette adresse e-mail est protégée contre les robots spammeurs. Vous devez activer le JavaScript pour la visualiser.

Religions, individuals and Native American communities in the United States

INTRODUCTION

Despite Native American history, Native American culture and religion are still prominent in the United States today, having been passed down through generations.

Before evaluating the place and role of Native American religion within American society, it will be interesting to first analyze to what point religion and beliefs are important inside Native communities, and then how through the different historical stages that they underwent, this culture has survived inside the United States of America.

Indian culture is a predominant factor in the entire Indian organizational structure. This aspect had rather negative repercussions from the very first contacts with Europeans, who at that moment had no time to devote to understanding the workings of the original inhabitants of these “new” lands. The cultural differences between the two communities gave rise to yet another polemical confrontation. As history would have it, the American hegemony “won the day”, and gradually imposed its modus operandi, including with surviving tribes, through genocidal episodes and the colonization of their territories.

It is highly likely that the survival of Native Americans, and the place they occupy in American society today, are in part linked to the importance of spirituality in their lives. The way Indians function depends on their ancestral philosophy, their attachment to their spiritual beliefs and the need to perpetuate and protect them. This aspect, despite the many attempts at colonial eradication, passed down from generation to generation, was also the reason why the Indians were able to demonstrate resilience; their cultural attachment being viscerally their reason for living.

I. What place is given to religion inside Native American communities?

First and foremost, it is important to understand the use of the word religion in a Native American context. In a very general and occidental definition, religion is a set of beliefs linked to practices. For Native Americans, it is rooted to their traditional culture, their way of thinking and living hence their philosophy, itself entertwined with the idea that everything is linked, the material and the immaterial, which therefore encroaches spiruality. There are no set limits, nor defines frames as it is possible to read when one wants to give a clear definition of these three words in Native American culture. Religion is connected to philosophy, itself connected to spirituality and conversely. Native American have no need to define limits between these three substantives. They experience it.

The use of the word religion in this analysis will remain faithful to the Native American conception, broadening our vision.

The scope of Native American religion has a deep ontological dimension. It is not only about believing, but it is more about a combination of being and living, integrating cultural values linked to the religious beliefs that are mainly based on the respect of all the elements, living or not living, surrounding the people, and seeing in them all the sacredness they contain. Everything is religious from birth to death, everything is seen as a whole. This way of integrating religion has historical, philosophical and societal roots.

A. The Historical Roots

Perhaps the most important aspect of indigenous cosmic visions is the conception of creation as a living process, resulting in a living universe in which a kinship exists between all things. Thus the Creators are our family, our Grandparents or Parents, and all of their creations are children who, of necessity, are also our relations. (Forbes, 2001:283).

It is difficult to find historical documents written by Native Americans themselves to describe their religions, their beliefs, their rites except for the winter counts, pictographic calendars mainly used by Plain tribes to relate the most significant events of a year. The cultural communication and the cultural transmission were principally oral from generation to generation.

The most genuinely and relevant knowledge that we have about Native American historical roots of their religion is from an empirical approach, what have been passed down through generations to maintain the upkeep of traditions, such as the fact that Native Americans do not have one single religion neither one single God. There are as many different belief systems as there are many tribes on the territory of what is the United States of America today. Hence, another element that makes the defining of Native American religion in a universal way quite impossible. It would require to incorporate all the different values, traditions and teachings of every Native tribe throughout the country into their own unique religious beliefs. They vary in their theories of creation; how nature and human beings came to exist and where they originated from. They use different traditions, with polytheistic views utilizing different gods (The Great Creator, Great Spirit, Earth Mother, Coyote…).

But there are also some similarities, like the belief of a creator, the belief that places and nature are important, as sacred and holy to celebrate ceremonies. Every tribe has rites linked to nature, the seasons, and the significant stages in human life from birth to death. Religion factored into all aspects of daily life; the natural and supernatural worlds are one in the same, completing each other, thus incorporating religion into everything. Traditions took on many similar forms between tribes: many different ceremonial dances, tribal gatherings and sacrifices of goods. Every tribe had a medicine man or shaman who possessed the power to engage the supernatural aspects more strongly, through visions and dreams. Also, most, if not all Native American religions functioned under some form of belief in animism alleging that a living spirit resides in all things, living or not: animals, materials, elements of nature such as the sun, the moon…

B. The Philosophical Roots

We Indians do not teach that there is only one God. We know that everything has power, including the most inanimate, inconsequential things. Stones have power. A blade of grass has power. Trees and clouds and all our relatives in the insect and animal world have power. We believe we must respect that power by acknowledging its presence. By honoring the power of the spirits in that way, it becomes our power as well. It protects us. (Means, 1995, P. 19).

In Native American philosophy, everything is related, everything is intertwined, from the material to the spiritual level. Everything has a reason for its existence, like every living being, and everything has been studied for centuries in an aetiological way, to understand the mystical and philosophical meaning of existence. Native American philosophy is deeply ontological based on studies and decades of observation to understand the essence of human existence. The use of language and the semiotic are also crucial to describe the depth of existence and its dimensions.

To understand the philosophy of Native American religion, it is important to underline the fact that the word “religion” has no exact translation as a real word in Native American languages, the common use to express the closest semantic would be with the word spirit, hence the Indigenous spirituality. Therefore, trying to give a definition of it is a way to narrow its semantic. The closest notion to describe Native American religion would be spirituality. It was a Western need, and/or a need from the circles of intellectuals to give a definition of it while the most concerned people have never considered to give one.

C. The Societal Roots

Thinking of ourselves in our sociality, or in our belonging to nature, it would be clear to say that for this indigenous conception of personhood or identity, an individual cannot be said to exist without the “people”—and we see how broadly this must be construed insofar as it includes all of our relationships. Insofar as personhood is extended not only to nonhuman animals, but even to the things of the world that are often considered inanimate, the question of who is to flourish is no longer about individuals within a structure that serves them, but rather the people as a whole. And that people as a whole is thus to be understood as the whole web of existence in which any singular being inheres. And here, we get a sense of how the ontological commitments of Native American philosophy overlap with the political commitments; in fact, I would argue, one cannot make sense of one without the other. (Arola, 2011:560).

Before colonization, Native American social structure was based on a tribal life, a group of people sharing the same culture and language, and therefore beliefs and spirituality, mainly linked to the environment they were adapted to. Most of the time, leaders were chosen by the members of the tribes mainly regarding his or her potential to protect their values. The matriarchal pattern was highlighted, since separation on any level did not exist, Native American women had a very impotant role inside the tribes. Concertation, and oral exchange were the key to take decisions or to settle a dispute. The group was like the backbone of tribal cohesion, in which everyone had a role to play. The notion of individuality did not prevail in Native American tribes. Collectivism was the societal pattern of functioning, but it had no need to be written or reminded by laws, it was a very natural conception of how the community should be held.

The Native American ontological approach to life, historically, philosophically, and socially led them to the conclusion that everything is linked, that separation does not exist. Everything works as a whole. That was the core of the antagonism between the European and mainly the British philosophy of life and the Native American one.

II. What place is given to Native American religion in the American Society?

This question is the core of what matters when one addresses the issue of religions, individuals and Native American communities in the United States. This subject has to be tackled in a chronological perspective to understand the various mechanisms of Native American adaptation, since it has been evolving from the first meeting with the settlers until present day.

A. The clash between two antipodean cultures

One of the primary differences between Europeans and Native Americans consists of the recognition and acceptance, by the Native American, that human beings are group beings and that, as such beings, they occupy specific locations that are their “rightful homes.” The Native American view is not, however, simply an “instinct” of territoriality. It is commonly known that the Native American found the concept of holding ownership of parts of the Earth quite alien. They did not think of their homelands as something they owned but instead as something that they belonged to. They thought of themselves as being “created” for one specific part of the planet. In an extension of this view they also included in their belief systems the idea that other <peoples, those unlike themselves, were also “created” for their own places. Each group was viewed as having a set of “truths” that pertained to their own unique circumstances and locales. (Cordova, 2002:5).

About 500 years ago, Europeans first made contact with Native Americans trying to find another route to the Indies. In 1607, the first English settlers arrived in Virginia, in what was going to be the first permanent settlement in North America. The indigenous people of the area were wary at first, then they helped them through a period of starvation. But the new settlers were interested in conquering new territories. As they were getting more numerous, they started to widen their occupation areas. Native population fought back. As they were many dead people on both sides, the settlers decided to implement the first agreements with written treaties. These agreements were therefore an unusual way for Native Americans to communicate, not always understanding what they would sign, and the English colonizers were starting to draw the foundations of what was going to be the United States of America using their own philosophical and social codes. They understood quite rapidly that Native Americans were not familiar with these codes, which made it easier to break the written treaties later on, and one by one. Simultaneously, they had fueled a form of contempt towards Native Americans who were commonly called “savage”. They did not understand their way of living, using only what was necessary from the wealth of the Earth, thinking it was out of lazyness. They did not understand the importance of all their life rituals. They failed to recognize any beliefs they had, and above all they were at the opposite of the collective view of the social organization of their communities. The settlers were bearing within them the premises of individuality, better known by the ideology of liberalism with the importance of the use of wealth on an individual scale.

Their evident eagerness to get more wealth, more land was not only a reason for disagreement with the Natives of the country, but also it was a deep philosophical dichotomy between the two civilizations.

As far as religion was concerned at that time, most colonists considered themselves as Christians. Native people had already had experienced different attempts of Christianization. The Spanish empire had sponsored the earliest missionary activity in the West, when the Franciscans had established the first missions in California in 1541 and New Mexico in 1581.

From the first encounters with the European settlers, Christianizing the Indigenous was not only a colonial approach but also an act of altruism since it was supposed to turn them into civilized people.

When the English settlers came to the “New World”, they were seeking to practice their Christianity in a theocratic totalitarian way. They were also concerned in widening their territory to do so. The question of Christianizing the Native Americans was officially and politically raised by the time of the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

The First Amendment of the United States Constitution, adopted in 1791, the first of the ten amendments that constitutes the Bill of Rights, promises freedom of religion:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. (U.S. Constitution First Amendment, 1791).

What truly was at stake at that moment was the importance for the Founding Fathers to detach from the British Crown power over religious matters. The first amendment goal was to protect their religion as the only religion, the other religions were not an issue:

The founding fathers’ religious settlement, embodied in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, gave legal sanction to an American revolution of religion that redefined the place of religion in America. With the exception of William Penn and RogerWilliams, the planters had organized church-state relations around the central idea of religious uniformity, the notion that the established church within a colony represented the one true religion that all should be compelled to support. Whether Puritans or Anglicans, the planters of a given colony shared a common faith, believed that their particular formulation of Protestantism was the correct one,[…]. (Franck, 2003:205-206).

One of the harshest periods for Native Americans was during the third American presidency, with Thomas Jefferson from 1801 to 1809, who believed in acculturation of Native people, giving up their cultures, religions, and lifeways and taking on the ways of white men, including Christianity and European-style agriculture and government. Jefferson believed that without this, Indians “will relapse into barbarism & misery, lose numbers by war and want, and we shall be obliged to drive them with the beasts of the forest into the Stony mountains.” (Letter to John Adams, 1812). He believed that assimilation of Native Americans into white economy would make them more dependent on trade, and that they would eventually be willing to give up land in exchange for goods or to resolve unpaid debts:

To promote this disposition to exchange lands, which they have to spare and we want, for necessaries, which we have to spare and they want, we shall push our trading uses, and be glad to see the good and influential individuals among them run in debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop them off by a cession of lands.... In this way our settlements will gradually circumscribe and approach the Indians, and they will in time either incorporate with us as citizens of the United States, or remove beyond the Mississippi. (Jefferson, 1803).

At the same time, he insidiously instituted federal paternalism toward the Natives of the country:

I take you and your people by the hand and salute you as my Children; I consider all my red children as forming one family with the whites, born in the same land with them, and bound to live like brethren, in peace, friendship, & good neighborhood. (Jefferson, 1809).

This was another way to express the superiority of the Anglo-Saxon and white civilization over the Indians.

Over the years, several doctrines fed the new mentality of superiority, legitimizing the excessive expansionism, ripping off the Natives of their land: the Doctrine of Discovery[i], the Monroe Doctrine[ii] followed by the Manifest Destiny[iii].

Federal agents chosen to tackle the “Indian question” belonging to the committee of Indian Affairs, then the Office of Indian Affairs were mandated to deal with these missions, signing treaties with the Indians to get more land and prevailing forced assimilation policy. These federal agents played an important part during the Removal Era (1830-1850), the removal of all tribes beyond Mississippi to the West of the country and the assimilation era (1880s-1930s).

B. The assimilation era

When a people is conquered and subject to another, it ceases to be a society, except in so far as it retains a spiritual life of its own apart from that of its conquerors. Yet it does not become an integral part of the victorious people's life until it is able to appropriate to itself the spirit of that life. So long as the citizens of the conquered state are merely in the condition of atoms externally fitted into a system to which they do not naturally belong, they cannot be regarded as parts of the society at all. They are slaves: they are instruments of a civilization of which they do not partake. […] The conquering society must be able to extend its own life outward, so as gradually to absorb the conquered one into itself; otherwise the latter cannot be regarded as forming a real part of it at all, but at most as an instrument of its life, like cattle and trees. (Mackenzie, 1890:Introduction).

Until present day, Native Americans have not incorporated the American way of life and hence the American society, at least not totally. There have been attempts of adaptation, most of the time to make sure they would ensure a form of tranquility in the face of the oppressor, it was a way of giving in and above all of surviving.

In 1819, the Civilization Fund Act[iv] was passed, with James Monroe as President. The law provided funding for the education of Native children, with the goal of introducing among them the habits and arts of American civilization. The funds were often given to church organizations that had already been active in trying to convert American Indians to Christianity. The churches used the government funds to establish day schools for Native children that were run by missionaries. These schools were located mostly on reservations and did not have housing for students. Children attended school during the day and returned to their communities at night. Mission day schools were the main educational institutions for Native children in the mid-1800s. The number of boarding schools remained small, however, until the 1870s. It was then that the government stopped funding mission schools and took a more direct role in Native education. It began establishing boarding schools on reservations and then off. Eventually, however, government officials decided that day schools were not well suited to the goal of assimilation because children were allowed to return to their homes at night. These officials determined that complete isolation would be a more effective way to break the children’s bonds with their communities, families, and cultures. They saw boarding schools as the answer.

Native American Boarding Schools first began operating in 1860 when the Indian Office (the previous name of the current Bureau of Indian Affairs) established the first on-reservation boarding school on the Yakima Indian Reservation in Washington State. Shortly after, the first off-reservation boarding school was established in 1879. The Carlisle Indian School located in Carlisle, Pennsylvania was founded by Richard Henry Pratt. Those schools were a preamble heralding the assimilation policy of the federal government towards Native people. In a very famous speech he gave in 1892, R.H. Pratt[v] stated, “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Brutal and often deadly, the schools stripped children of their language, culture, communities and above all their families. It was thought and expected that the separation made it easier to make the children forget their language and culture. The children were taught Christian beliefs, and forced to adopt American habits and customs. The government believed that Native American traditions got in the way of the assimilation of the children. In 1887, the U.S. Congress passed a law, the Federal Compulsory School Attendance for all Indians[vi], requiring Native children to attend school. After that, the agents pressured parents who were reluctant to cooperate by withholding food or other supplies. If necessary, they sent police to seize children.

Meanwhile, in 1883, Hiram Price was Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He was in charge of how the government treated Native Americans. Price created a set of rules. They became known as the Code of Indian Offences. The code made many traditional Native American religious practices like dance ceremonies against the law. If people broke the law, they might not get food or be sent to prison, or worse get killed. These punitive decisions were taken by federal agents. One of the saddest examples would be the massacre at Wounded Knee on December 29th, in 1890, where the Lakota people continued to dance despite the code. Not only was it seen as a federal offence, but also as a threat by the federal agents; about 300 Native people were killed on that day by the US Army. These civilization regulations were meant to decide how Native Americans ought to be, outlawing anything that had to do with their original culture, stripping them of everything about them that was Native through deculturization, and starting with children sending them to the sadly famous Native boarding schools, that had one goal, processing Indian children into non-Indian children. Native American religion, spirituality and philosophy were no longer acknowledged as something to exist on the American territory. It had to vanish, such as the terminology used at that period with “the myth of the vanishing Indian[vii]”.

The assimilationist period was active in two areas, the anthropological level, and the social behavior. It was meant to eventually merge the Native Americans into the American mainstream of that time. They were supposed to mingle with the American society and civilization and in doing so they would leave their land behind; which would enable the federal government to act on the second area, the territorial aspect. To exert sufficient pressure on that aspect, the government passed laws to ensure that the land of Native people was sold to non-Native people. This started by the mid-century discovery of gold and silver in the West, as well as new federal legislation such as the Indian Appropriations Act of 1851[viii], which forcibly moved Indigenous groups onto Indian reservations decided by the government, then with the Homestead Act of 1862[ix] and the Dawes Act of 1887[x], respectively signed by Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Grover Cleveland, breaking up Indigenous lands further and privatized them for sale to white settlers. As the century continued, American settlers further encroached on the ever-shrinking territories of Indigenous groups, most of time in bloody genocidal battles. Native American sacred places and land were sold or became public domain. Their souls were sold too, since their beliefs and spirituality were deeply linked to their environment, hence their Native land.

This era was probably one of the worst eras for Native American people as far as the cultural loss was concerned. It led to traumas that were passed on through generations until present day. It left the Native people exhausted, stunned, disenchanted, resigned, deeply touched in their souls. To survive, most of them internalized what the “civilized” men taught them to do.

The assimilation period was a disaster, many children died at boarding schools from diseases and bad treatments. It was also a period of profound social despair for Native American communities, they were the poorest, the sickest, the least educated and qualified…but still they had survived despite all extermination efforts. The Indian question had to be tackled differently.

C. Towards cohabitation

“Cohen believed that Indian reservations held a promise for a better national future-a future that would implement his legal pluralist vision.”, (Mitchell, 2007:74). Felix Cohen, a federal agent of the Department of the Interior from 1933 to 1947, was appointed to draft the core of the Indian legislation during the era of the Indian New Deal. The Civilization Regulation got withdrawn and tribal rights were recognized. He worked with the Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, John Collier, to draft the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934[xi], an act that was meant to widen tribal sovereignty, for the tribes who would adopt the reorganization proposed in the Act and hence being recognized as federal tribes, that would give them the right to get federal grants and would also open different collaborations on political, legal and economic levels. It was the beginning of new relations between the federal government and the new tribal governments.

This new policy was a radical reversal, in intention if not always in effect, comparing to all the previous U.S. government policies toward American Indians. The IRA of 1934 dramatically changed policy by allowing tribal self-government and consolidating individual land allotments back into tribal hands. Collier set out his vision for what became known as the Indian New Deal to decrease U.S. federal control of Native affairs and instead allowed for Native self-determination and self-governance.

Not all tribes adopted the IRA, nor did all tribal members of those that did adhere to this new paternalistic order of the federal government, which allowed them to be recognized as tribes only if they accepted the proposed organization. The Indians could organize into self-governing communities under Federal supervision only, and with extension of responsibility as Indians show capacity for self-rule. There was also a great deal of mistrust of this new government, which despite its demonstrated political efforts, had no real impact to erase the traumas and betrayals of the past.

This attempt to reconcile the federal government with Indian tribes did not last very long. In the 1950s, the government's budgetary priorities changed. The expensive New Deal policy was strongly criticized. It was a perfect moment for the Eisenhower[xii] administration to announce the Termination policy in 1953, regarding Native Americans. It meant to give them more autonomy by cutting federal grants, and adding relocation programs for them when they would decide to leave their reservation to live in the American cities. It was the last attempt of the federal government to push the Native people into adopting the American mainstream, because this time again, it did not work; it made them even poorer and alienated them. This policy faded by the mid-1960s, and was officially stopped in the 1980s with the Ronald Reagan’s statement on Indian policy on January 24th 1983[xiii], when he explicitly rejected any further Termination policy towards Indian people.

As far as the cultural beliefs and religion were concerned, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act[xiv], or AIRFA, in 1978, was a first big step forward for Native American cultural protection. All Indian cultural and spiritual practices were protected and allowed. The law also recognized that the government had been preventing these practices, admitting that it had also kept Native Americans from their holy sites and objects.

In 1990, Congress passed the Native American Languages Act[xv], to preserve and protect Native American languages and all their cultural aspects, giving grants to the tribal governments that would implement language learning programs.

In 1993, The Religious Freedom Restauration Act[xvi], strengthened the previous AIRFA ordering the government to let Native Americans use their holy sites, and practices, reinforcing the protection of these sites.

It took decades for the U.S. government and all the agents appointed to deal with the Indian issue, to figure out the relevant attitude to have towards Native Americans, to get rid of them, to push them to the West, to ignore them politically, legally, economically. When it came to the cultural aspect, it was about assimilated the survivors in a forced messianic way. Since the end of the XXth century, the states have created Tribal Affairs Offices to implement government-to-government relationships, based on dialogue and consultation, including Native Americans in all the social issues, participating in the country's political, economic and cultural life.

III. Native American religion as a means to survive in the American Society

The Europeans have had an extraordinarily difficult time in understanding the structure, substance, and procedures of the Indian manner of governing their societies. […]. Others have suggested that religious beliefs and cultural patterns have prevented Indians from organizing themselves socially or politically in a fashion familiar and acceptable to European minds. (Deloria & Lytle, 1998:17).

The two decades leading up to the 1980s saw the end of the assimilationist policies of the 1950s for Indians. The counter-cultural movements in the United States with the civil rights movement in the 1960s gave Indian activists the opportunity to make their voices heard, after a century of “silence” due to the contempt with which their demands had been treated up to that point. The opening of the first Indian casinos on Indian lands gave the tribes a de facto new economic, political and cultural status.

A. Economically

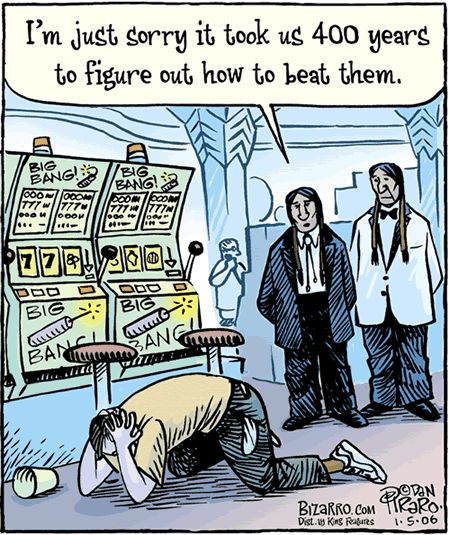

Created by Dan Piraro Bizarro Comics, 1, 5, 2006

Before the arrival of the settlers, the Indians' economic system was limited to self-sufficiency. They hunted, sowed and harvested what they needed to live, and they would exchange with other tribes surplus goods. They were masters of sustainable environmental engineering, using cutting-edge farming techniques to respect the earth and ensure that every offering returns to it, so that the next generations would have the same access to the richness of the environment. This was due to a strong belief that they had to give back everything they would take, so that Mother Earth would continue to make its riches available. For a long time, external factors to the economic development of Indian tribes were a brake. Physical, territorial, political and legal oppression led to their almost total marginalization, preventing many of them from attaining a decent economic level, until present day. Despite the colossal profits made by casinos, the latest in-depth economic studies do not reveal a sufficiently significant and uniformly positive economic change among Indian tribes. The Indians continue to pay the price for inequalities imposed more than a century ago[xvii].

After several years of litigation, the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA)[xviii] of 1988 formalized and legalized casinos on tribal lands. This law gave tribes undeniable economic sovereignty, which did not leave the states indifferent. This new freedom was not without its problems, and many state obstacles were put in place to prevent casinos from opening. It is only since the early 2000s, more than 12 years after the signing of the IGRA, that some tribes have been able to enjoy the full benefits of the law, while paying percentages of their profits to the counties and the state according to their agreements, which vary according to the sales and size of the casinos.

These millions of dollars in circulation are social levers that compensate for the shortcomings of the states and the country in terms of social assistance, but also reduce geographical economic inequalities, given that the casinos are located on Indian lands, themselves isolated from the major economic centers.

Still, the economic consideration of the country's Natives became indispensable. The political and legal changes of the 1960s were at the root of this turning point. At the time, the American tribes had not yet built up sufficiently strong and successful forces to weigh in the country's economic balance. However, the new political and legal measures led them to position themselves economically too, as these three areas were intrinsically linked. Since then, conscious of this era of innovative reforms in their favor, Native Americans have seized the moment to organize and aggregate to form groups and associations with common economic goals and interests.

By legalizing this new economic windfall for the tribes, the U.S. government also granted them a form of economic sovereignty, albeit subject to paternalistic conditions. Certainly, they acquired capital giving them access to greater freedom, while being obliged to contribute to the social needs of the surrounding communities, and thus support non-Indian populations. Since the history of colonization of American lands, the opening of casinos on these same lands has been the most important upheaval with numerous human repercussions. Despite certain pernicious aspects, casinos today are synonymous with hope and change for Indian Nations and tribes:

The effects of tribal gaming on American Indian nations have been profound. Kevin Washburn (2008), Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs at the US Department of the Interior, has said, “Indian gaming is simply the most successful economic venture ever to occur consistently across a wide range of American Indian reservations”. (Akee, Spilde, Taylor, 2015:185).

B. Politically

What we did in the 1960s and early 1970s was raise the consciousness of white America that this government has a responsibility to Indian people. That there are treaties; that textbooks in every school in America have a responsibility to tell the truth. An awareness reached across America that if Native American people had to resort to arms at Wounded Knee, there must really be something wrong. And Americans realized that native people are still here, that they have a moral standing, a legal standing. From that, our own people began to sense the pride. (Dennis Banks, March 14th 1996, activist and co-founder of the American Indian Movement (AIM), during his speech “His Aim is True”).

The two great assimilationist periods for Native Americans in the USA, from 1887 to 1934 with the Dawes Act or General Allotment Act, then from the 1950s to the end of the 1960s during the Termination period, forced Indians to leave their reservation lands to acculturate to the American mainstream. These policies were implemented under the guise of altruistic concern on the part of the government to legitimize these acts. This did not dampen the resolve of the main protagonists targeted, to organize themselves into more radical movements and defend their rights on a political scale.

This form of political or at least politicized organization was not a given in the Amerindian way of life. As already mentioned, the Amerindians did not possess a political organization as hierarchical and structured as that of the European colonists. However, after decades of attempted neantization, the country's Natives had to fight back by organizing and aggregating themselves according to a model that was foreign to them, in order to be heard.

Despite the continuity of Indian political organization, the Termination Act was signed in 1953[xix], followed by the Indian Relocation Act of 1956[xx], forcing reservation Indians to move to metropolises such as San Francisco and Los Angeles. This enabled them to concentrate their forces and become a decisive element in the Indian movement of the following decade. The Indian response became more radical, and the term Red Power Movement was coined.

Parallel to the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the radicalization of the Red Power Movement culminated with the creation of activist groups, such as the American Indian Movement (AIM) in 1968. It was also the period when powerful and impactful demonstrations and acts of protest took place such as the 1969 seizure of Alcatraz Island, the 1972 Trail of Broken Treaties with the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in Washington D.C., and the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee. These events went beyond the scope of Indian pacifist protests. The most famous, the occupation of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay on November 20, 1969, lasted 19 months. It was a highly publicized event at the time, and helped to alert public opinion nationally and internationally. During the occupation, a group of Indian demonstrators revisited land claims, deplorable living conditions on the reservations, the need for tribal independence and the official end to the policy of Termination. On the spot, the hundred or so demonstrators decided to form the pan-Indianist group Indians of all Tribes (IOAT).

Since the occupation of Alcatraz Island - a decisive turning point, if not the turning point, in the Red Power Movement's new dimension - Indian political influence was reversed: from the non-existent phase, it was embodied by the determination of the movement and its leaders. This determination reached all the way to the highest political echelons. The various protest actions reiterated the pressure that had been brought to bear, serving as a reminder of the determination that animated the dissident Indian community at the time.

There is no doubt that the Indian community has had a political influence on the national scene. It began, and continues to exist, because the Indians were willing to follow colonial politics in terms of organization. Their voices were repeatedly heard, especially as they became increasingly vocal and impossible to ignore, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. Legitimately, American governments were willing to make a few societal, environmental, educational and cultural concessions in those same years. However, there are many obstacles to pan-Indian effectiveness. It is difficult to envisage a harmonious agreement between all the tribes towards convergent demands, both in terms of manner and substance. As mentioned earlier, each tribe has its own beliefs, customs and spirituality. There are certainly some convergences and similarities, but pan-Indianist models, particularly political ones, blend all these specificities to which tribal members are attached.

The current challenge for tribal governments and their leaders is to perpetuate this relatively recent political influence while protecting their tribal values. Today, it is possible to be optimistic for Native Americans about the direction that the governance of the country and the states seems to be taking in terms of consideration. They are present on all the issues of governance that fall to them: sovereignty, territory, environment, culture, health, women's and children's rights. Political agreements are made following genuine consultation, with a deep mutual desire to respect each other's interests, legal decisions are no longer systematically anti-Indian, and economic partnerships are the hallmark of genuine collaboration. The number of Native Americans elected to key positions in the country's governance has increased over the last two decades.

C. Culturally

“The contributions that Native Americans have made to our Nation’s history and culture are as numerous and varied as the tribes themselves,” he said. “This year gives us the opportunity to recognize the special place that Native Americans hold in our society, to affirm the right of Indian tribes to exist as sovereign entities, and to seek greater mutual understanding and trust”, (Georges H.W. Bush, November 2001, during his speech for the National American Indian Heritage Month proclamation).

During George H.W. Bush[xxi]'s term in office, several laws protecting Indian culture and identity were passed: the National Museum of American Indian Act[xxii] (NMAIA), the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act[xxiii] (NAGPRA) and the Native American Languages Act[xxiv] (NALA). This period accentuated the importance of Native American cultural heritage, and the need to preserve it within American society.

As noted earlier, the Indian cultural sphere has always been a predominant domain of the entire Indian organizational structure. This aspect was one of the fundamental antagonisms from the earliest contacts with Europeans, who had no time to devote to understanding the workings of the original inhabitants of these highly coveted lands. Cultural differences between the two communities provided yet another bone of contention on which to clash. As history would have it, the American hegemony “won the day”, and gradually established and even imposed its own way of operating, including within the Native American communities.

It took several decades for tribal governments to officially follow the American political model, with the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) in 1934, described above. The notion of government was new to the country's Indians. No such structure existed in tribal organization. They had not felt the need to create governments. Their modus operandi was based on communal understanding, trust and homogeneity. Each tribe had its own intrinsic individuality rather than structural differences. As a result, they saw no need to formalize an American mode of governance.

Even today, IRA governments are not fully accepted by all tribal members, who see them as a form of state interventionism. This is a reality. They feel that this obligation to organize according to a model that does not belong to them is yet another form of intrusion that does not correspond to their cultural values.

This American influence on Indian culture annoys many tribal members for two main reasons: they reject the culture of a civilization that has plundered their wealth mainly out of greed, but also out of a sense of superiority; they fear losing the authenticity linked to their identity, itself linked to their culture, by adopting American habits.

However, to qualify for tribal recognition and federal subsidies, tribes have to fit the IRA government model. This injunction to organize regarding this model not only had deleterious effects on the evolution of the Indian community. It accelerated all aspects of the community's development. The economic boost provided by the state enabled certain tribes to achieve real development, which in turn enabled the Indians of the United States to gain a place on the political scene, and then to create a legal organization. Although this was done under American influence, many tribes adopted these models, while at the same time enabling them to regain more sovereignty and hence retaining their cultural customs, originality.

Religiously speaking, the Native American Church (NAC), or the practice of Peyotism, officially declared in 1918, is one of the most influential religious practices and spiritual movement among tribes in the United States today, since 63% are Christian[xxv]. It is also one of the most telling examples of Native American adaptation since it is a syncretic combination of Christian and Native American beliefs. It seems that thanks to some kind of covenant between Native Americans and American institutions, on the economic and political levels, which allowed a form of acculturation and, more importantly, peace in these various compromises, Native Americans have gained the ability to exercise a form of sovereignty and continue to practice, preserve and transmit their beliefs, their spirituality, their vision, and hence their religion.

Conclusion

“We’re still here”, is one of the most widely used motto by Native Americans, as to mock the predictions of the XXth century, according to which they were meant to completely disappear.

The U.S. government is no longer actively trying to get rid of Native American culture. Instead, it has been working to collaborate actively with the tribes involving them in the political, economic and cultural patterns of the American society.

On the Native American side, it is a (hi)story of adaptation and compromise since the early colonial time, by their own choice, then by force, and today as part of an integration process to live together while preserving and passing on all aspects of their culture.

Economically, they have adapted intelligently and wisely especially thanks to the success of their casinos, since most of their customers are non-Indians, they reuse the concept of greed reaping the rewards.

Politically, they organized themselves following the IRA patterns to be federally recognized to have a chance of collaborating with local, state and federal governments of the country.

Culturally and “religiously” they adopted some Christian aspects, mixing them with Native American spirituality, both in their beliefs and practices.

The threat would be to see Native American spirituality disappear behind more Westernized currents of thought.

Thanks to recent economic powers, from the benefits of the casinos, which have enabled a new political recognition, tribes have more means today to keep their own culture existing. Numerous tribal cultural groups have organized across the country over the past two decades to regain control over the passing on of cultural knowledge, whether in tribal schools, evening classes or weekend workshops. The aim is to continue to pass on tribal beliefs through ancient counts, to pass on tribal language, knowledge of the surrounding flora and fauna, how to cultivate each plant and its health benefits, artistic knowledge, basket-making, jewelry, pottery... These initiatives have created a new dynamic linked to Native American resistance within the tribes, but also among non-Indian citizens, who seem to be increasingly interested in the culture and spirituality of their country's Natives.

Today, legal protection in the United States in terms of Native American individual rights are fairer. It is important to bear in mind that all the traumatic experiences that they have been passed down from generation to generation, continue to impact Indigenous communities until present day. They still have the highest rate of depression or suicide in the country. It is also essential to restore pride in Native heritage to reduce the downward spiral and all the social side effects that are not all resolved for Native new generations, looking up to their cultures, rehabilitating their place in the American society, will help the healing of these two civilizations to continue to live together.

After all, the Native American strongest spiritual belief according to which everything and everyone are connected to each other as a whole, might eventually find a relevant resonance.

Endnotes

[i] The Doctrine of Discovery gave religious authority, since the expression was used by Popes in the 15th century, at the beginning of European colonial expansion, to invade and subjugate non‐Christian lands, peoples and sovereign nations, to impose Christianity on these populations, and to claim their resources, since Christianity was superior to any religious belief.

[ii] The Monroe Doctrine was articulated by the President Monroe 1823, to emphasize the interests of the United States and demanding the Europeans not to interfere in U.S. policy.

[iii] The Manifest Destiny, a phrase used in 1845, by John Louis O'Sullivan, an American columnist and editor. The idea was that the United States was destined by God to expand its dominion and spread democracy and capitalism across the entire North American continent. The philosophy drove 19th century U.S. territorial expansion and was used to justify the forced removal of Native Americans from their homes.

[iv] Public Law No. 15–85, 3 Stat. 516b (March. 3, 1819)

[v] Richard Henry Pratt (1840-1924) was a soldier in the American Civil War and later fought in armed conflicts against Native Americans on the Great Plains.

[vi] 26 Stat. 989,25 U.S.C. § 284.

[vii] The Myth of the Vanishing Indian was a national self-fulfilling prophecy pursued by federal government officials and agents throughout the 19th century that aligned with a wider expansionism belief, with the idea that American territorial expansion by white settlers was both inevitable and preordained by God, also believing that Indigenous peoples would eventually disappear.

[viii] Thirty-First Congress. Session II Chapter XIV, February 27th 1851.

[ix] Act of May 20, 1862 (Homestead Act), Public Law 37-64

[x] Act of February 8th 1887, Public Law 49–105

[xi] Act of June 18th 1934, Public Law 73–383

[xii] Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961, as a Republican.

[xiii] Ronald Reagan Presidential Library & Museum, Statement on Indian Policy, https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/statement-indian-policy.

[xiv] Public Law No. 95–341, 92 Stat. 469 (Aug. 11, 1978)

[xv] Public Law No. 101–477, 104 Stat. 1152 (Oct. 30, 1990)

[xvi] Public Law No. 103–141, 107 Stat. 1488 (Nov. 16, 1993)

[xvii] Housing Needs On Native American And Alaska Native Tribal Lands, National Low Income Housing Coalition, March 8th 2024, file:///C:/Users/Utilisateur/Downloads/Native-Housing-2024.pdf

[xviii] Public Law No. 100–497, 102 Stat. 2467 (Oct. 17, 1988)

[xix] House concurrent resolution 108

[xx] Public Law No. 84–959, 70 Stat. 986 (Aug. 3, 1956)

[xxi] George H.W. Bush (1924-2018) was the 41st president of the United States from 1989 to 1993, as a Republican.

[xxii] Public Law No. 101–185, (Nov. 28, 1989)

[xxiii] Public Law No. 101–601, 104 Stat. 3048 (Nov. 16, 1990)

[xxiv] Public Law No. 101–477, 104 Stat. 1152 (Oct. 30, 1990)

[xxv] 2023 PRRI Census of American Religion: County-Level Data on Religious Identity and Diversity, https://www.prri.org/research/census-2023-american-religion.

Bibliography

Akee Randall, Spilde Catherine A., Taylor Johnathan B. (2015). “The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and its Effects on American Indian Economic Development . Journal of Economic Perspectives”, Vol. 29, no3, 2015:185.

Arola Adam, (2010). “Native American Philosophy”. Garfield J and Ederglass W. The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy. New York:Oxford University Press:562-573.

Cordova V. F. (2002). “Bounded Space: The Four Directions”, APA Newsletters, Vol. 2, n°1, fall 2002, Newsletter on American Indians in Philosophy:5

Deloria Vine Jr. & Lytle Clifford M. (1998). The Nations Within: The Past and the Furture of American Indian Sovereignty. Austin:University of Texas Press:17.

Forbes Jack D. (2001). “Indigenous Americans: Spirituality and Ecos”, DAEDALUS, Journal of the Academy of Arts and Sciences, fall 2001:283-300. [URL:https://www.amacad.org/publication/daedalus/indigenous-americans-spirituality-and-ecos. Seen September 11th 2024]

Founders Online. “From Thomas Jefferson To Indian Nations, 10 January 1809”. National Archives. [URL:https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-9516. Seen August 30th 2024]

Lambert Frank, (2003). “The Founding Fathers and the Place of Religion in America”, Princeton: Princeton University Press:205–06.

Mackenzie John S. (1890). An Introduction to Social Philosophy.Glascow:Maclehose.

Mitchell Dalia Tsuk (2007). Architec of Justice:Felix S. Cohen and the Founding of American Legal Pluralism. Ithaca:Cornell University Press:74.

Russell Means, (1995).Where White Men Fear to Tread:The Autobiography of Russell Means. New York:St Martin’s Press.

U.S. Constitution First Amendment, (1789). Congress.gov, [URL:https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/amendment-1. Seen September 10th 2024]

The US Dakota War of 1862. Jefferson to William H. Harrison, 1803. Minnesota historical society. [URL:https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/thomas-jefferson. Seen September 1st 2024]

Pour citer cet article :

Fondville, R. (2025). Religions, individuals and Native American communities in the United States. RITA (18). Mise en ligne le 15 novembre 2025. Disponible sur : http://www.revue-rita.com/articles-n-18/religions-18-varia.html

Pour accéder au fichier de l'article, cliquez sur l'image PDF ![]()

Avec le soutien du LER-Université Paris 8

Avec le soutien du LER-Université Paris 8